Why Note-Taking Often Fails: The Illusion of Learning and Three Better Alternatives

Walk into almost any secondary classroom today and you’ll find a familiar scene: students facing a projected slide deck, copying line-by-line whatever appears on the screen. At first glance, this looks like learning. Students are busy. Pens are moving. Paper is filling up with information. And as teachers, we feel good—after all, students now “have the notes.”

But having notes and learning from notes are two very different things.

For many students, traditional note-taking—especially transcription-based note-taking—creates only the illusion of learning. It feels productive but offers little long-term impact on memory or understanding. And for years, cognitive science has been remarkably consistent about this: passive note-taking produces weak learning gains, while active retrieval produces durable learning gains.

In this post, I want to unpack why copying notes from slides is so ineffective, why it often leads to inflated confidence, and what we can replace it with if we’re serious about strengthening memory, deepening understanding, and supporting long-term retention.

I’ll reference research throughout, including ideas from my presentation 10 Ways We Get Retrieval Wrong, which you can explore on your own.

The Note-Taking Problem: Copying ≠ Thinking

The core issue with transcription-based note-taking is simple: it requires almost no cognitive effort.

Students don’t have to transform, organize, evaluate, or connect information—they simply transfer text from Point A (the slide) to Point B (their notebook). This is a fundamentally passive act, and passive acts build weak memories. It also teaches students that passively writing notes – or passively reading notes over and over will help increase performance.

Shallow Processing Leads to Fragile Learning

In my 10 Ways We Get Retrieval Wrong presentation, I name this problem directly: shallow processing results in “low cognitive effort” and “weak neural connections.”

This aligns with decades of cognitive psychology research. When the brain isn’t working hard, it doesn’t encode material robustly. Memories built through low effort fade quickly. They remain fragile, susceptible to forgetting. Next time you are visiting some place you’ve never been, resist the urge to enter the destination in your GPS and listen to turn-by-turn directions to navigate you there. By reviewing a map, intently watching for landmarks and street names, making the wrong turn and recovering from that mistake, you’ll immediately find you remember the directions much more than you would if you listened to turn-by-turn directions to navigate you there. The cognitive demand required to manually navigate strengthens new neurons and makes them more resistant.

The Fluency Illusion: Feeling Like We Know Something When We Don’t

Transcribing notes also creates what Robert Bjork calls the fluency illusion—the tendency to mistake familiarity for understanding. When students see the same information repeatedly (on slides, in their notebooks), the content feels familiar. That familiarity can produce a sense of mastery.

In reality, nothing durable has been stored.

Fluency ≠ understanding. Recognition ≠ recall.

This is why many students are confused when they read their notes over and over but still perform poorly on their assessment.

How Students Typically Study Notes—and Why It Doesn’t Work

Consider what many middle and high school students actually do when preparing for a test. I see this repeatedly, and I’ve watched it with my own 8th grader: students sit down, open their notes, and simply read them over and over again.

They believe that rereading equals studying.

They believe that exposure equals memory.

They believe that familiarity equals readiness.

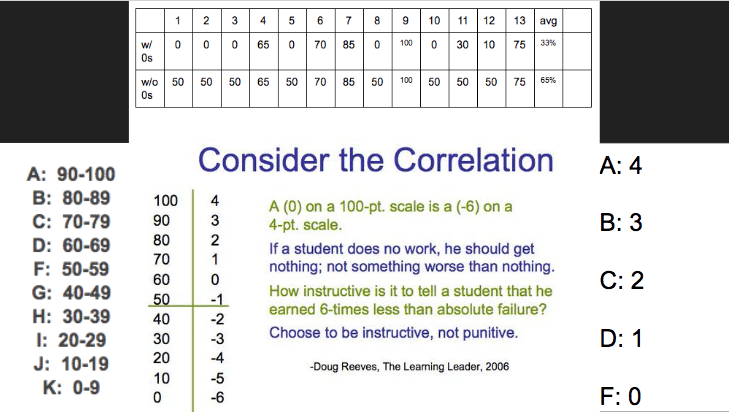

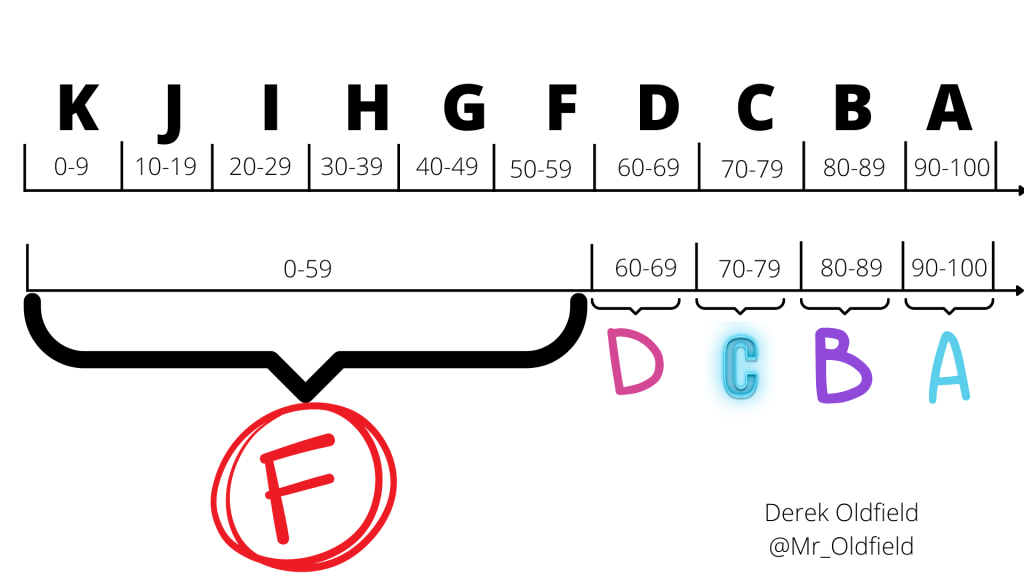

But rereading is one of the least effective study strategies available. In a landmark study, Roediger & Karpicke (2006) found that students who reread learned far less than students who retrieved—even if the rereaders felt more confident. Students need to know that rereading isn’t the same as testing yourself. There is zero retrieval involved in rereading notes.

Rereading improves retrieval strength temporarily—students can recall information in the moment because it’s fresh—but it does little to build storage strength, which determines whether students will remember the information days or weeks later.

This also connects directly to Bjork’s distinction between retrieval strength (short-term accessibility) and storage strength (long-term durability). Notes that are only reread do not increase storage strength at all.

Rereading notes is like going to the gym, watching everyone else work out, and expecting to get stronger.

You’re near the action, but the work isn’t being done by you.

What Actually Builds Memory? Effort + Retrieval

Durable learning is the result of effortful thinking. When the brain has to struggle—just a bit—to retrieve or reconstruct information, the memory trace becomes stronger.

Decades of research support this:

-

Effortful retrieval strengthens both retrieval strength and storage strength (Bjork, 1994).

-

The act of pulling information out of memory is what consolidates it (Roediger & Butler, 2011).

-

Generation effects show we remember more when we generate information ourselves rather than receive it (Slamecka & Graf, 1978).

Simply put:

The brain remembers what it works on, not what it copies.

Why Student-Created Notes Outperform Teacher-Provided Notes

Now, this does not mean that notes have no value. Notes can be powerful—but only when students are creating, transforming, or organizing ideas themselves. This has to be explicitly taught to students.

Student-Created Notes Require Cognitive Demand

When students must:

-

summarize information in their own words,

-

make decisions about what is important,

-

connect new ideas to prior learning,

-

sketch, map, or represent relationships,

they are engaging in deeper processing—what Craik & Lockhart called levels of processing theory. This kind of note-taking is cognitively demanding and therefore memory-strengthening.

Student-Created Notes Activate Retrieval Systems

Creating notes forces students to:

-

pull from memory,

-

articulate meaning,

-

reconstruct concepts,

—all of which strengthen learning.

These are note-taking strategies, too—just not the traditional, passive kind.

Three High-Impact Alternatives to Traditional Note-Taking

Below are three research-based strategies that outperform transcription and align with what we know about retrieval, memory, and long-term retention.

✅ Brain Dumps (Free Recall)

What it is:

Students close their notes and write down everything they remember about a topic, concept, or lesson.

Why it works:

-

It forces retrieval—the strongest known strategy for improving long-term learning.

-

It surfaces misconceptions.

-

It increases both retrieval strength and storage strength.

Research Base:

Roediger & Karpicke (2006) demonstrated that retrieval practice significantly outperforms rereading in long-term retention.

How teachers can use it:

-

Begin class with a 2–3 minute brain dump on yesterday’s lesson.

-

After a unit, ask students to brain-dump everything they know about the topic before reviewing.

-

Pair students to compare and add missing ideas.

This single strategy outperforms hours of rereading.

✅ Student-Generated Questions

What it is:

Students create test questions, quiz questions, or “What might the teacher ask?” questions about the content.

Why it works:

Creating questions requires deep sensemaking. Students must understand the content well enough to identify what is important and how to ask about it.

How teachers can use it:

-

Have students create three multiple-choice and two short-answer questions after a lesson.

-

Build a class Kahoot, Wayground (Quizizz), or Gimkit from student-generated items.

-

Use student questions in warm-ups or exit tickets.

Question-generation turns passive receivers into active thinkers.

✅ Concept Mapping or Schematic Notes

What it is:

Students transform notes into a diagram, map, or visual representation of how ideas connect.

Why it works:

Concept mapping forces students to organize and structure information—deep processing that strengthens memory pathways.

How teachers can use it:

-

Replace “Copy this definition” with “Create a diagram showing how these three ideas connect.”

-

Have students turn a page of notes into a visual map at the end of class.

-

Use concept maps as a warm-up to reactivate prior knowledge.

Concept mapping transforms information into understanding.

Small Shifts Teachers Can Make Tomorrow

You don’t have to overhaul your classroom to make note-taking more meaningful. Here are a few small, high-leverage shifts:

-

Don’t put full sentences or complete explanations on slides.

This forces students to think, not copy. -

Use retrieval before teaching.

Ask, “What do you already know about…?” before showing anything. -

Replace “Copy this down” with “Summarize this in your own words.”

-

Stop assuming students know how to study.

Teach them how to retrieve, not reread. -

Integrate short, low-stakes retrieval every day to strengthen memory gradually rather than cram before assessments.

These subtle changes dramatically increase cognitive demand, memory strength, and comprehension.

Closing: Moving From Teaching Notes to Teaching Learning

Note-taking, as it is traditionally done in many classrooms, offers little return on investment. It feels safe, predictable, and efficient—but it leaves students with fragile memories, inflated confidence, and minimal long-term retention.

The goal of schooling is not to produce pages of well-organized notebooks.

It’s to build thinkers with durable, flexible knowledge.

When we shift from passive transcription to active retrieval, we honor the way the brain actually learns. We help students strengthen the neural pathways required for recall. We equip them with study strategies that will serve them far beyond our classrooms.

And we give them something more valuable than beautiful notes—we give them the ability to remember, understand, and apply what they’ve learned.