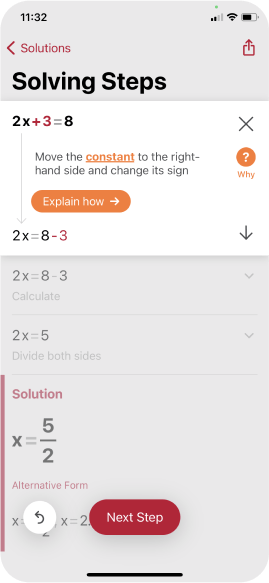

I think middle and high school English teachers are facing a moment that math teachers have faced for a number of years. Years ago, tools like PhotoMath and Wolfram Alpha became accessible for students. These tools allow students to scan math problems and it will provide them the answer with the steps worked out.

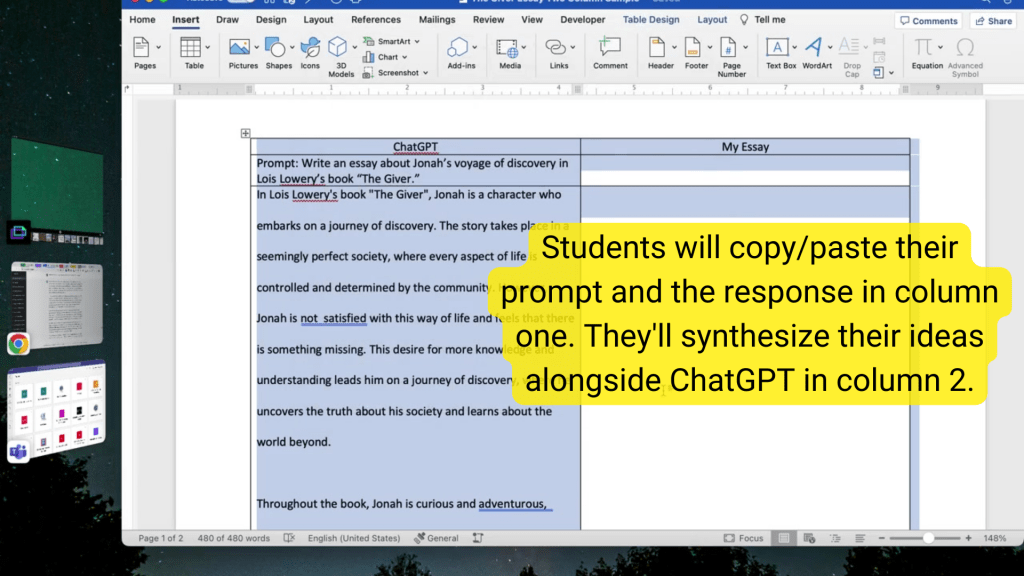

These tools have ignited calls in the math teaching community to engage in math practice that requires critical thinking and fuels sense-making, while assigning less work focused on Bloom’s Taxonomy verbs of solve, simplify, and calculate. I believe English teachers are facing the same reality right now given that students can generate text so easily with tools like ChatGPT. Will English teachers be more inclined to shift practice if the content standards update? I used to feel that may be the case, but let’s develop what’s currently happening. I think English teachers must now adapt to the ubiquity of AI-generated text. Students are using ChatGPT and similar Ai tools, whether we want them to or not. So I believe English teachers are on the cusp of being more intentional about using generative Ai to support student writing. I’m a big fan of the strategy where learners create a two-column paper and copy-paste ChatGPT’s response in one column, then the students synthesize their own response in the second column.

This strategy may become more favorable because it requires students to be open and transparent about using ChatGPT, juxtaposing Ai-generated text with their own ideas and expansions. I believe we’re nearing a moment where teachers won’t have a choice but to adopt this strategy and others. I don’t want to sound naive, either. There are plenty of teachers navigating these decisions now, but many school districts are playing catch-up with policies, while there are still concerns about student safety and compliance with FERPA and COPPA.

There have been pivotal moments throughout history where new technology was initially feared, but eventually became an accepted part of learning. Calculators in math classrooms are one such example. But we can go back even further and see that it’s fairly common for society to experience some measure of panic about new media. In 1936, St. Louis Missouri tried to ban car radios for fear that drivers would become too distracted. In 1926, The Charlotte News reported that the personal radio was keeping children up late at night and causing harm due to lack of sleep. In 1898, The New York Times panned that Thomas Edison’s phonograph would lead to fear of expression among boys. I’m not suggesting some of the recent fears around new media and technology don’t have merit, nor am I trying to minimize those pouring energy into studying the effects of new media on our young learners. Perhaps there are legitimate concerns that should be taken seriously. My point is, society has historically shifted for better or worse.